Clash of Champions Season 2, Pythonized

30 September 2025

It's been a month since the second season of Clash of Champions' final episode. While the games were entertaining and the questions were interesting to try out along, I decided to take things up a notch and decided to rest my mind from straining due to logic and code some Python instead.

In this write-up, there are two games that I tried coding in Python and I thought are worth explaining: Viral Protocol and Logic Race.

Viral Protocol

You can watch the original episode here.

The game starts with 16 people, each assigned to one of the four roles: carrier, immune, infected, and healthy. The main task is to figure out the assignment of every single player in the game, not just oneself.

There are two phases in the game: logical statements, and asking questions.

- Logical statements: you will be given 20 logical statements for you to make preliminary deductions

- Asking questions: in turns, each player gets to ask for the role of a particular player, say player X. Then, a question of either pictorial, quantitive, or palindromic category will be selected and the whole player in the game must answer the particular question. If player X is the fastest to answer correctly, the role of player X will be revealed to only X, otherwise it will be such to all the players who answered correctly.

The earlier you gain more correct deductions, the more bonus points you gain, but this is specific to the game itself and I only wanted to solve the logical statements.

Let's start with the list of logical statements that was shown in the game.

1. There are 4 Immune patients.

2. One of the patients 1, 3, 7, 8 is Healthy and another one a Carrier.

3. There are no Infected patients sequentially after a Healthy one.

4. Between patients 1 to 4, two of them are Infected.

5. Between patients 13 to 15, only one of them is Infected.

6. The status of each of patients 14 and 7 is different with those of each of patients 11 and 5.

7. The status of each of patients 1 and 4 is different with those of each of patients 2 and 15.

8. Neither of the patients 5, 12, and 16 are Immune.

9. The status of patients 7, 8, 13 are pairwise distinct.

10. If patient 1 is not Immune and patient 14 is not Infected, then patient 16 is not Healthy.

11. There are 4 Carrier patients.

12. Only one of the patients 3, 6, 13, 15 is Immune.

13. If both patients 6 and 11 are Immune, then patient 9 is not Infected.

14. Carrier patients are numbered multiples of 4.

15. There are more Infected patients than Carrier patients.

16. Infected patients are odd-numbered.

17. The status of patients 4, 7, 10, 11 are pairwise distinct.

18. Patients 15 and 11 have a different status than patient 10.

19. There are no more Healthy patients than those Immune.

20. If patient 10 is not Immune, then patient 14 is a Carrier.

Using pure deduction and no guesswork, you can deduce at most 14 of them right away. I'll leave that as a practice for you readers.

Now that we have our logical statements, let's start coding! Begin with defining some enums like CARRIER, IMMUNE, INFECTED, and HEALTHY for readability.

CARRIER = 1

IMMUNE = 2

INFECTED = 3

HEALTHY = 4

We want to represent our answer as a list of 16 integers, each being an integer in $[1,4]$. Next, we will use a backtracking function to try out different assignments in this list and then validate the answer once we have reached the end of the list.

ans = [1]*16

def backtrack(ans, idx):

if idx == len(ans):

if check(ans) == -1: print(ans)

return # stop backtracking

for val in range(1, 5):

ans[idx] = val

backtrack(ans, idx+1)

def check(ans):

... # to be defined later

The backtracking function keeps track of the index of ans, idx, that you want to try filling the values on. If you're done with idx, you move on to idx+1. Therefore, it makes sense to put idx == len(ans) as the base case and validate your answer when this is reached. The for loop tries to fill ans[idx] which each of the 4 values available.

The validation function check(ans) is rather simple in concept but tedious to implement due to the many logical statements. My plan is for this function to return one of the rule number it violates and -1 otherwise, i.e. no violation. If the return value is indeed -1, then I can simply print the answer in the backtracking function. This way, it will print all the valid solutions instead of just one.

Take note that indexing starts from 0, so I had to subtract the patient numbers by 1. For example, the status of patient 5 in ans would be represented as ans[4]. Another example would be patient with numbers being multiples of 4 will have their indices equivalent to 3 modulo 4. Also, some rules were reordered for slight optimization and readability.

from collections import *

def check(ans):

# checking on status of specific patients

if ans[4] == IMMUNE or ans[11] == IMMUNE or ans[15] == IMMUNE: return 8

if (ans[0] != IMMUNE and ans[13] != INFECTED) and (ans[15] == HEALTHY): return 10

if (ans[5] == ans[10] == IMMUNE) and (ans[8] == INFECTED): return 13

if ans[14] == ans[9] or ans[10] == ans[9]: return 18

if ans[9] != IMMUNE and ans[13] == CARRIER: return 20

for i in range(len(ans)-1):

if ans[i] == HEALTHY and ans[i+1] == INFECTED: return 3

for i in range(len(ans)):

if ans[i]==CARRIER and i%4!=3: return 14

if ans[i]==INFECTED and i%2!=0: return 16

# checking on number of distinct status relationships using Python set

if {ans[13], ans[6]}&{ans[10], ans[4]}: return 6

if {ans[0], ans[3]}&{ans[1], ans[14]}: return 7

if len({ans[6], ans[7], ans[12]}) != 3: return 9

if len({ans[3], ans[6], ans[9], ans[10]}) != 4: return 17

c = Counter(ans)

# checking on quantity of overall status using Counter

if c[IMMUNE] != 4: return 1

if c[CARRIER] != 4: return 11

if c[INFECTED] <= c[CARRIER]: return 15

if c[HEALTHY] > c[IMMUNE]: return 19

# checking on quantity of a specific status using Counter

t = Counter([ans[0], ans[2], ans[6], ans[7]])

if t[HEALTHY] != 1 or t[CARRIER] != 1: return 2

t = Counter(ans[:4])

if t[INFECTED] != 2: return 4

t = Counter(ans[12:15])

if t[INFECTED] != 1: return 5

t = Counter([ans[2], ans[5], ans[12], ans[14]])

if t[IMMUNE] != 1: return 12

# all good!

return -1

To implement the validation function check, you definitely need a Counter to tabulate the frequencies of a subset of the patients in your assignment. Each of the return statements are checking if the opposite of the logical statement is true. For example, on rule 20 that says If patient 10 is not Immune, then patient 14 is a Carrier., the opposite of would be Patient 10 is not Immune and patient 14 is not a Carrier., which translates to if ans[9] != IMMUNE and ans[13] == CARRIER: return 20.

While pruning can be done to optimize the code even more, the techniques are not generalizable for this question, because if the logical statement changes, the pruning methods used will differ. Therefore, we'll leave pruning out of scope for the sake of simplicity.

Combining all that we have above, the final Python code becomes like this.

CARRIER = 1

IMMUNE = 2

INFECTED = 3

HEALTHY = 4

def backtrack(ans, idx):

if idx == len(ans):

if check(ans) == -1: print(ans)

return # stop backtracking

#if idx%4 == 3: return backtrack(ans, idx+1)

for val in range(1, 5):

ans[idx] = val

backtrack(ans, idx+1)

from collections import *

def check(ans):

# checking on status of specific patients

if ans[4] == IMMUNE or ans[11] == IMMUNE or ans[15] == IMMUNE: return 8

if (ans[0] != IMMUNE and ans[13] != INFECTED) and (ans[15] == HEALTHY): return 10

if (ans[5] == ans[10] == IMMUNE) and (ans[8] == INFECTED): return 13

if ans[14] == ans[9] or ans[10] == ans[9]: return 18

if ans[9] != IMMUNE and ans[13] == CARRIER: return 20

for i in range(len(ans)-1):

if ans[i] == HEALTHY and ans[i+1] == INFECTED: return 3

for i in range(len(ans)):

if ans[i]==CARRIER and i%4!=3: return 14

if ans[i]==INFECTED and i%2!=0: return 16

# checking on number of distinct status relationships using Python set

if {ans[13], ans[6]}&{ans[10], ans[4]}: return 6

if {ans[0], ans[3]}&{ans[1], ans[14]}: return 7

if len({ans[6], ans[7], ans[12]}) != 3: return 9

if len({ans[3], ans[6], ans[9], ans[10]}) != 4: return 17

c = Counter(ans)

# checking on quantity of overall status using Counter

if c[IMMUNE] != 4: return 1

if c[CARRIER] != 4: return 11

if c[INFECTED] <= c[CARRIER]: return 15

if c[HEALTHY] > c[IMMUNE]: return 19

# checking on quantity of a specific status using Counter

t = Counter([ans[0], ans[2], ans[6], ans[7]])

if t[HEALTHY] != 1 or t[CARRIER] != 1: return 2

t = Counter(ans[:4])

if t[INFECTED] != 2: return 4

t = Counter(ans[12:15])

if t[INFECTED] != 1: return 5

t = Counter([ans[2], ans[5], ans[12], ans[14]])

if t[IMMUNE] != 1: return 12

# all good!

return -1

# the actual answer from the game

ACTUAL = [3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1]*2

ans = [1]*16

#ans[3] = ans[7] = ans[11] = ans[15] = 1

backtrack(ans, 0)

Very interestingly, there is more than one valid answer to this as shown in the output of running the above code.

$ python main.py

[3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 2, 2, 3, 1, 3, 4, 4, 1]

[3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1]

[3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 4, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1]

Also, note that when I bypassed rule 11 and 14, the backtracking becomes much faster. You can uncomment the lines if idx%4 == 3: return backtrack(ans, idx+1) and ans[3] = ans[7] = ans[11] = ans[15] = 1 that pre-assigns the four patients to the Carrier status and then skips these indices during backtracking. You can test it out for yourself, mine ran in about 10 seconds as shown below. Without this commenting, the code might take way longer. (Theoretically, if fixing 4 values yields 10 seconds, then not doing that might make the code run for $10 \cdot 4^4 = 2560$ seconds which is about 42 minutes)

$ time python main.py

[3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 2, 2, 3, 1, 3, 4, 4, 1]

[3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1]

[3, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1, 4, 2, 3, 1, 3, 2, 4, 1]

real 0m10.081s

user 0m10.077s

sys 0m0.004s

Logic Race

You can watch the full episode here. (congrats, Vannes!)

You can also try out the game yourself here!

It all went down to the final game of the season and I actually came to the watch party of the final episode during the Final Chapter event, which was, without a doubt, not a regret.

As the announcer showed how the Logic Race game works, my mind instantly thought of the Queens game on LinkedIn. Pretty sure you've tried it once-- right? Corporate workers?? LinkedIn warriors??

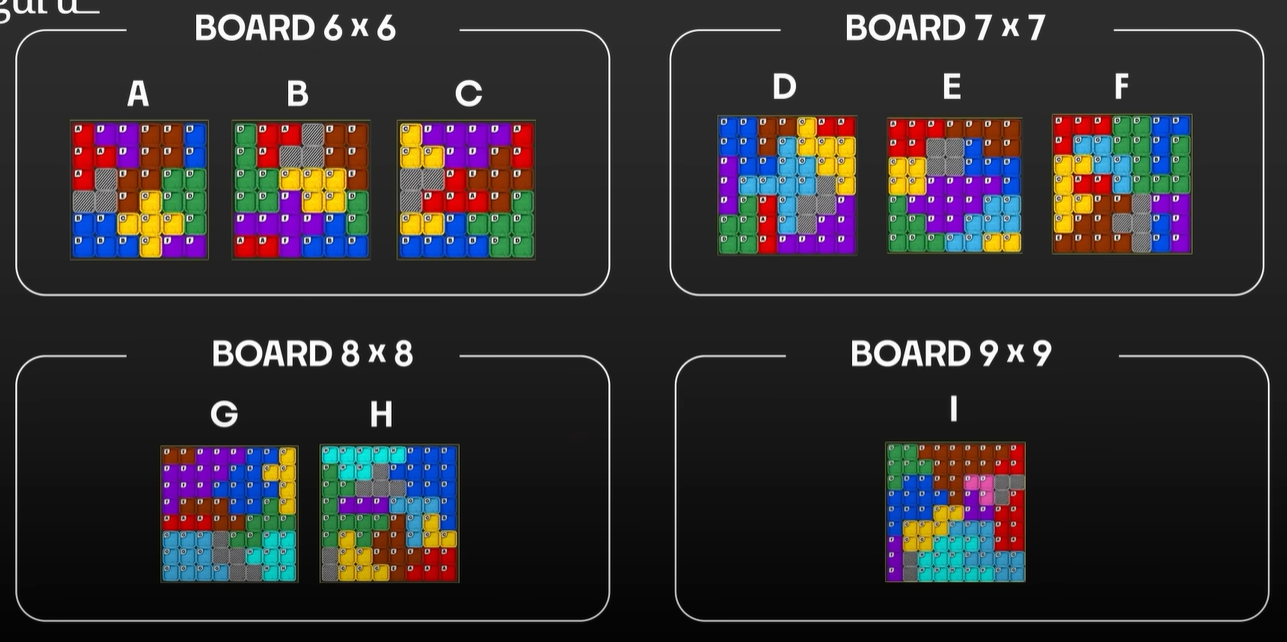

Anyways, while it's not exactly 100% like Queens, it is more complex and more challenging for an obvious reason. The regions of the same colour can be disconnected and some cells may be invalid on top of the usual no-two-queens-can-attack rule. There are multiple boards of various sizes to be solved, and the first to solve all boards wins. (Take note that the Queens game on LinkedIn has a small rule difference: two pieces can lie on the same diagonal, just not diagonally adjacent)

Without further ado, let's see how the boards look like.

Technically, this question can be solved with backtracking as well!

Let's start with modelling the board in Python. I eventually used a multistring like the following example. Assume I have a function solve(board, title) that takes in the board representation and the board label, and solves that particular board.

def solve(board, title):

... # to be defined later

solve('''

AFFEEB

AAFEEB

AXEEDD

XXECDD

BBCCCD

BBBCFF

''', 'A')

Next, a function to parse the board. I wanted it to return a mapping from the region labels (excluding the invalid cells) and the cell positions it occupies, as well as the dimension of the board itself since it varies.

def parse(board):

new_board = {}

board = board.strip().split('\n')

for i in range(len(board)):

for j in range(len(board[0])):

ch = board[i][j]

if ch == 'X': continue

if ch not in new_board: new_board[ch] = []

new_board[ch].append((i, j))

return new_board, len(board), len(board[0])

For example, parsing board A above will give us this representation.

({'A': [(0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (2, 0)],

'B': [(0, 5), (1, 5), (4, 0), (4, 1), (5, 0), (5, 1), (5, 2)],

'C': [(3, 3), (4, 2), (4, 3), (4, 4), (5, 3)],

'D': [(2, 4), (2, 5), (3, 4), (3, 5), (4, 5)],

'E': [(0, 3), (0, 4), (1, 3), (1, 4), (2, 2), (2, 3), (3, 2)],

'F': [(0, 1), (0, 2), (1, 2), (5, 4), (5, 5)]},

6, # rows

6) # columns

Using this new representation of the board and the board dimensions, we can display/print it nicely so we don't have to strain our eyes.

Suppose we have our finalized assignment of the pieces, and we also want to show them. One way is to override our displayed board with a bunch of * at the positions of the pieces.

def display(board, rows, cols, asg={}):

ans = [['X']*cols for _ in range(rows)]

for i in board:

for r, c in board[i]: ans[r][c] = i

for i in asg:

r, c = asg[i]

ans[r][c] = '*'

print('\n'.join(map(''.join, ans)), end='\n\n')

So, let's say we display our parsing result above. The code will be able to print the original board again.

AFFEEB

AAFEEB

AXEEDD

XXECDD

BBCCCD

BBBCFF

If we set the last parameter asg = {'A': (0, 0), 'B': (5, 2)}, the output will become as shown below.

*FFEEB

AAFEEB

AXEEDD

XXECDD

BBCCCD

BB*CFF

We're done with the convenience functions, which means we're left with the backtracking.

The goal is to ensure that each of the distinct letters (excluding 'X') has a cell assigned to it, while respecting the fact that there can only be one piece on each row, each column, and each diagonal.

Similar to what we did on Viral Protocol, instead of going through the indices/patients, we go through the letters, keeping track which rows have been used, which columns have been used, which diagonals have been used. Suppose for each of these we have a set to keep track, namely row, col, dip, and din (the final two stands for diagonal-positive and diagonal-negative).

Whenever we add an assignment at position (r, c) for a letter, we have to add r to row to indicate that row r has been taken. Similarly, c to col, r+c to dip and r-c to din. Note that two pieces on the same diagonal will have either the same r+c value or the same r-c value, depending the direction of the diagonal, so this storing makes sense.

Once you add the respective values to the sets that keep track of the current assignment, we move on to the next letter. If we're done with backtracking the next letter, we revert our assignment and trackr sets to the original state by discarding the same values that were added.

The difference with the backtracking at Viral Protocol is that we can validate our current assignments on-the-go instead of having to wait until the base case idx == len(letters). Once there are two pieces with the same r value, or same c value, or same r+c value, or even same r-c value, then the whole assignment is invalid.

import time

def solve(board, title):

tstart = time.time()

board, rows, cols = parse(board)

letters = sorted(

board,

# heuristics on which colour

# to try first?

key=lambda x: len(board[x])

)

def bt(idx, asg={}, row=set(), col=set(), dip=set(), din=set()):

if idx == len(letters):

return display(board, rows, cols, asg)

let = letters[idx]

for r, c in board[let]: # try all positions

# validate on-the-go

if r in row: continue

if c in col: continue

if r+c in dip: continue

if r-c in din: continue

# assign and add to tracker sets

asg[let] = (r, c)

row.add(r)

col.add(c)

dip.add(r+c)

din.add(r-c)

# continue backtrack

bt(idx+1, asg, row, col, dip, din)

# remove from tracker sets and undo assignment

din.discard(r-c)

dip.discard(r+c)

col.discard(c)

row.discard(r)

asg.pop(let)

print('='*20+'\n')

print('BOARD', title)

print('\nInitial board:')

display(board, rows, cols)

print('Solution(s):')

bt(0) # start at index 0 of the letters list

print('Solved in', round(time.time()-tstart, 5), 'seconds\n')

print('='*20)

One optimization I can think of now is to sort the letters by the number of cells the letter occupies. If we work on the easier letters, we can terminate our backtracking faster, which might influence our solving speed. This heuristic is interestingly also a strategy that humans might use!

I also added some functionality to print out the elapsed time just because. Maybe to see how much faster the algorithm can do it better than humans can...?

Anyways, wrapping up everything, we have the following Python code. After the backtracking comes the 9 boards from the game so you don't have to recreate the boards yourself again.

def parse(board):

new_board = {}

board = board.strip().split('\n')

for i in range(len(board)):

for j in range(len(board[0])):

ch = board[i][j]

if ch == 'X': continue

if ch not in new_board: new_board[ch] = []

new_board[ch].append((i, j))

return new_board, len(board), len(board[0])

def display(board, rows, cols, asg={}):

ans = [['X']*cols for _ in range(rows)]

for i in board:

for r, c in board[i]: ans[r][c] = i

for i in asg:

r, c = asg[i]

ans[r][c] = '*'

print('\n'.join(map(''.join, ans)), end='\n\n')

import time

def solve(board, title):

tstart = time.time()

board, rows, cols = parse(board)

letters = sorted(

board,

# heuristics on which colour

# to try first?

key=lambda x: len(board[x])

)

def bt(idx, asg={}, row=set(), col=set(), dip=set(), din=set()):

if idx == len(letters):

return display(board, rows, cols, asg)

let = letters[idx]

for r, c in board[let]: # try all positions

# validate on-the-go

if r in row: continue

if c in col: continue

if r+c in dip: continue

if r-c in din: continue

# assign and add to tracker sets

asg[let] = (r, c)

row.add(r)

col.add(c)

dip.add(r+c)

din.add(r-c)

# continue backtrack

bt(idx+1, asg, row, col, dip, din)

# remove from tracker sets and undo assignment

din.discard(r-c)

dip.discard(r+c)

col.discard(c)

row.discard(r)

asg.pop(let)

print('='*20+'\n')

print('BOARD', title)

print('\nInitial board:')

display(board, rows, cols)

print('Solution(s):')

bt(0) # start at index 0 of the letters list

print('Solved in', round(time.time()-tstart, 5), 'seconds\n')

print('='*20)

solve('''

AFFEEB

AAFEEB

AXEEDD

XXECDD

BBCCCD

BBBCFF

''', 'A')

solve('''

DAAXEE

DAXXEE

DDCCCE

DDFCCD

FFFFBD

AAFBBB

''', 'B')

solve('''

CFFFFA

CCFFEA

XXAEEE

XAAAED

CCBDDD

BBBBDD

''', 'C')

solve('''

BBEECAA

BBEGCCC

FBBGGCC

FGGGGXC

FDAGXXF

DDAGXFF

DDAFFFF

''', 'D')

solve('''

AAAEEEE

AAXXBEE

CCXXBBB

CCFFFFB

DFFFFGG

DDFFGGG

DDDGGCC

''', 'E')

solve('''

AAADDBB

AGGDDBD

CCGGDBD

CAAGDDD

CCEEXFF

CEEXXBF

EEEEXBF

''', 'F')

solve('''

EEFFFBBC

FFFFBBCC

FFFBBBBC

FEEEBBDC

AAAEEDDD

GGGXDDHH

GGGXXHHH

GGGGXXHH

''', 'G')

solve('''

HHHHHBBB

DHHXBBBB

DDXXXBBB

DFFFGGGB

DDDDEGCB

DCDEEGCC

XCCEEEAA

XCCCEAAA

''', 'H')

solve('''

DDEEEEEEA

DDDEEEEAA

DBBEEIIXX

BBBBEFIXA

BBBCCFFAA

BCCCGGGAA

FCCHHHGAA

FXHHHGGGG

FXHHHHHGG

''', 'I')

Running the above code conveniently gives us all the solution(s) to each board.

====================

BOARD A

Initial board:

AFFEEB

AAFEEB

AXEEDD

XXECDD

BBCCCD

BBBCFF

Solution(s):

AFFE*B

AA*EEB

*XEEDD

XXECD*

BBC*CD

B*BCFF

Solved in 0.00022 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD B

Initial board:

DAAXEE

DAXXEE

DDCCCE

DDFCCD

FFFFBD

AAFBBB

Solution(s):

DA*XEE

DAXXE*

D*CCCE

DDFC*D

*FFFBD

AAF*BB

Solved in 0.00025 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD C

Initial board:

CFFFFA

CCFFEA

XXAEEE

XAAAED

CCBDDD

BBBBDD

Solution(s):

CFF*FA

*CFFEA

XXAE*E

X*AAED

CCBDD*

BB*BDD

Solved in 0.00056 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD D

Initial board:

BBEECAA

BBEGCCC

FBBGGCC

FGGGGXC

FDAGXXF

DDAGXFF

DDAFFFF

Solution(s):

BBE*CAA

B*EGCCC

FBBGGC*

FGGG*XC

FD*GXXF

*DAGXFF

DDAFF*F

Solved in 0.00029 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD E

Initial board:

AAAEEEE

AAXXBEE

CCXXBBB

CCFFFFB

DFFFFGG

DDFFGGG

DDDGGCC

Solution(s):

AAAEE*E

A*XXBEE

CCXX*BB

*CFFFFB

DFF*FGG

DDFFGG*

DD*GGCC

Solved in 0.00051 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD F

Initial board:

AAADDBB

AGGDDBD

CCGGDBD

CAAGDDD

CCEEXFF

CEEXXBF

EEEEXBF

Solution(s):

A*ADDBB

AGGD*BD

*CGGDBD

CAA*DDD

CCEEXF*

CE*XXBF

EEEEX*F

AAAD*BB

*GGDDBD

CCGGD*D

CAA*DDD

C*EEXFF

CEEXXB*

EE*EXBF

Solved in 0.00052 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD G

Initial board:

EEFFFBBC

FFFFBBCC

FFFBBBBC

FEEEBBDC

AAAEEDDD

GGGXDDHH

GGGXXHHH

GGGGXXHH

Solution(s):

EEF*FBBC

FFFFBB*C

FFFB*BBC

FE*EBBDC

*AAEEDDD

GGGXD*HH

GGGXXHH*

G*GGXXHH

E*FFFBBC

FFFFBBC*

FFFBB*BC

*EEEBBDC

AA*EEDDD

GGGX*DHH

GGGXXH*H

GGG*XXHH

Solved in 0.00065 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD H

Initial board:

HHHHHBBB

DHHXBBBB

DDXXXBBB

DFFFGGGB

DDDDEGCB

DCDEEGCC

XCCEEEAA

XCCCEAAA

Solution(s):

HHH*HBBB

DHHXBBB*

*DXXXBBB

DF*FGGGB

DDDDE*CB

D*DEEGCC

XCCEEE*A

XCCC*AAA

Solved in 0.00177 seconds

====================

====================

BOARD I

Initial board:

DDEEEEEEA

DDDEEEEAA

DBBEEIIXX

BBBBEFIXA

BBBCCFFAA

BCCCGGGAA

FCCHHHGAA

FXHHHGGGG

FXHHHHHGG

Solution(s):

*DEEEEEEA

DDDE*EEAA

DBBEEI*XX

B*BBEFIXA

BBBCC*FAA

BC*CGGGAA

FCCHHHGA*

FXH*HGGGG

FXHHHHH*G

DDEEE*EEA

DD*EEEEAA

DBBEEI*XX

B*BBEFIXA

BBB*CFFAA

BCCCGGG*A

*CCHHHGAA

FXHH*GGGG

FXHHHHHG*

DDEEE*EEA

DD*EEEEAA

DBBEEI*XX

B*BBEFIXA

BBB*CFFAA

BCCCGGGA*

*CCHHHGAA

FXHHHGG*G

FXHH*HHGG

Solved in 0.00122 seconds

====================

On top of being blazing fast, we can also see that some boards have multiple valid solutions, and only one is needed to solve the entire board. This is a rather unique insight since most of the audience will think there is a unique solution for each board.

That's all the backtracking fun! I hope you gained an insight or two on how Python backtracking can be implemented. Time to lock in for another month before I can come up with another write-up. (hopefully...)